Deliverance in the Data

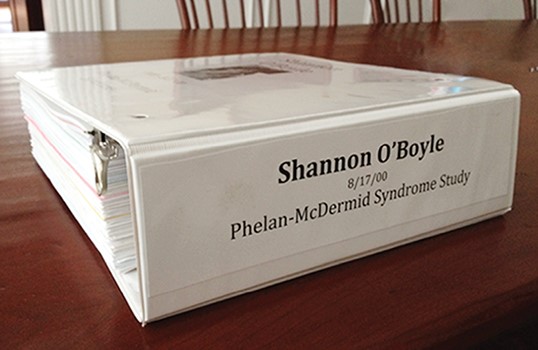

Megan O’Boyle keeps track of her daughter Shannon’s medical records using this voluminous binder, which she takes to Shannon’s doctor’s appointments. (All photos provided by Megan O’Boyle.)

Megan O’Boyle with daughter Shannon

Megan O’Boyle presents data from the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome registry in May 2015 at the International Meeting for Autism Research.

In 2014, Megan O’Boyle participated in a discussion at a meeting of the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke Non-Profit Forum.

Mother’s Crusade to Help Daughter with Genetic Syndrome Leads to Work in Health Data Analytics Research

The American healthcare system was seemingly built around the needs of patients and their families. Likewise, advancements in electronic health records and health IT evolved to meet the needs of providers who deliver care to increasingly complex patient populations. While “knowledge is power,” in too many cases, there are numerous barriers separating those two things.

Megan O’Boyle knows these barriers well. As the mother of a child with a rare debilitating genetic syndrome called Phelan-McDermid Syndrome, gathering and maintaining the records kept by prestigious hospitals in the northern Virginia suburbs of Washington, DC where they live has presented numerous physical and financial hurdles. With providers as far away as Philadelphia, PA, O’Boyle has always had to stay organized in order to ensure her daughter was properly cared for. Now, as the principal investigator of the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome International Registry and the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Data Network—initiatives of the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Foundation—O’Boyle heads an endeavor that advocates for current patients as well as future generations of newly diagnosed patients by collecting and using their health information to improve care and contribute to Phelan-McDermid Syndrome research.

‘Thrown in the Deep End of Data’

O’Boyle’s daughter Shannon, who will turn 18 this year, was born with Phelan-McDermid Syndrome and requires 24-hour care. The severity of the symptoms varies from patient to patient, but Shannon is considered to have a severe intellectual disability. Shannon is mobile in that she doesn’t require a wheelchair, but she is nonverbal and thus very limited in how she can communicate. Testing has found that cognitively she has the understanding of a two-year-old, though her mother believes she can understand nearly everything that is said and explained to her. Like other individuals with Phelan-McDermid Syndrome, Shannon has suffered from seizures that are now considered well-controlled with medication, although for some patients seizures can be uncontrolled and seemingly drug-resistant. A majority of patients with Phelan-McDermid Syndrome are also diagnosed with autism.

As is typical of the condition, Shannon has had up to 15 different healthcare providers who all address different symptoms and complications of the syndrome, which can include sleep disturbances, gastrointestinal problems, attention deficit disorder, dental issues, epilepsy, and renal system disturbances. Some also suffer from heart defects—such as a hole in the heart—or kidney defects.

Shannon was diagnosed in 2001 when she was eight months old. The diagnosis, which requires genetic testing to confirm, is also known as 22q13 Deletion Syndrome. It is the result of a missing piece of genetic material on chromosome 22 which usually includes the SHANK3 gene, or sometimes a mutation of the SHANK3 gene itself, according to the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Foundation. O’Boyle says the foundation knows of at least 1,800 families with a family member diagnosed with Phelan-McDermid Syndrome, with only 800 of those families living in the United States.

The disease is so rare that there is no ICD-10 code for it, which makes collecting data for the pursuit of treatments and cures that much more difficult. O’Boyle says that when a child is diagnosed by genetic counselors, parents end up heading to an internet search engine and find the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Foundation, the only formal organization in the United States dedicated to the disease.

O’Boyle says she first joined the foundation strictly for the moral support and shared experiences that it provides to other families affected by the disease. But in 2010, she was approached by another parent involved with the foundation and asked if she’d be interested in helping create a Phelan-McDermid Syndrome registry. In the world of rare diseases, the creation of registries is vitally important in helping identify how many people share the condition worldwide, characterizing the condition, and providing a mechanism to recruit for research studies and clinical trials. It also helps put the disease on the map for researchers studying cures, causes, and treatments for this disease and the dozens of other conditions it’s related to. At first, O’Boyle was tentative to commit to the offer.

“I said ‘I don’t even know what a registry is. I’ll do a newsletter or raise money, but research isn’t my thing. I don’t think it [research] will help my daughter in her lifetime. I’m not interested,’” O’Boyle says. “Finally, I asked her [the other mom] if she was asking me because I live near the National Institutes of Health, and she said ‘Yes. We need someone who can go to meetings and learn more about what we need to do.’ I’m the least likely parent to be thrown in the deep end of data. Back then, I didn’t know what Big Data was, or what a registry was,” O’Boyle admits with a laugh.

But 18 months later, with the help of a registry “boot camp” sponsored by the Genetic Alliance, the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Foundation launched the first Phelan-McDermid Syndrome International Registry, where O’Boyle is listed as the principal investigator, a full-time volunteer position.

Health Records Vital to Data Research, But Often Hard to Obtain

O’Boyle and many other parent volunteers involved in the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Foundation spend more than 40 hours a week on foundation-related tasks. Because their kids’ condition is so rare, research into treatments might never happen without their advocacy and work.

O’Boyle reached out to Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy to help model the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome International Registry after theirs. She also talked to genetic researchers to find out what kind of data they look for when pursuing treatments. Not having any formal data analytics training prior to serving as the data registry’s principal investigator, O’Boyle set out to learn on the job. “I did not receive any formal training for my current position. From 2010 to present I have attended meetings and workshops on related topics, reached out to experts in the field, and called upon other disease groups for guidance,” she says.

In order to improve the quality of the answers the families would provide in the registry questionnaires, the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Foundation held training for families on how to collect and organize their medical records. The premise being that if you have the medical record in front of you when you are filling out the questionnaire, then your answers will be more accurate and thus the data in the registry will be more accurate.

O’Boyle knows firsthand what families are up against when trying to collect enough of their children’s records just to coordinate and continue ongoing care.

“I did it myself first and I’m in the [Washington] DC area, not dealing with rural hospitals, but major hospitals. I called four of the many [hospitals] I’ve interacted with and got four sets of answers. Some departments charged a quarter a page [for health record copies], or 50 cents per page, or $1.43 per page. I get that there’s a cost to this. My father was a physician. I understand that in small pediatrics practices that someone has to stop working at the front desk to make copies. I just don’t think that the costs should fall on the patient or caregiver who’s already paid their insurance premium and paid their copays. It’s like going back to the same well three times,” O’Boyle says.

Complicating matters, there was no uniformity in providers’ procedures for obtaining health records, or simply how they referred to their health information management (HIM) departments. “Generally, the staff in the medical records departments are polite and informative. Unfortunately, they do not create the policies for the retrieval of medical records or determine the cost that goes along with it, so I imagine that they hear the frustrations of the patients and caregivers,” O’Boyle says.

She notes that this time-consuming process is especially fraught for parents of children whose care is an all-consuming task in its own right. “Truly our families have a hard time getting a shower. You cannot leave your child in front of a television. Somebody has to be watching them. It’s just not feasible for them to give up hours to chase down records,” O’Boyle says.

Fortunately, the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Foundation received funding in 2013 through an award from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) to collect patient medical records and incorporate them with existing parent-reported data from the registry as part of the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Data Network. This allowed the foundation to outsource the collection of medical records to a third-party organization. That organization would request all the records, track all the consents, and then upload the records to a database. This help came after the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Foundation had some families do a beta test of sorts by trying to get all the needed documentation from patient portals.

While the portals should have simplified things, this also turned out to be far more complicated than they first thought, especially since parents were requesting information for children who were over the age of 12 or 13—the age at which, in some practices, the portals are turned over to the patient’s control. Teenagers with Phelan-McDermid Syndrome, however, are unable to provide verbal or written consent allowing their parents to see everything in their portal. So in addition to requesting records, the parents were also asked to provide documentation of their child’s intellectual disability before they could acquire the records they needed. Even without this barrier, portals generally do not provide the data that families and researchers truly need in rare diseases. They need access to the actual notes, the “story,” not just the vital signs and labs.

O’Boyle says that the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Foundation is the only organization working to find out how many people worldwide have been diagnosed with the genetic syndrome. Typically, the diagnosed find their way to the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Foundation, not the other way around.

With the award money from PCORI, the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Data Network partnered with Harvard Medical School in 2013 to integrate data from the patient registry with knowledge derived from clinical notes of the electronic health records of syndrome patients. The Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Data Network’s mission is to advance knowledge of the syndrome and related conditions and to accelerate the translation of that knowledge into care and treatments leading to improvements in meaningful health outcomes, according to the project summary on the data network’s website. This is accomplished by integrating complex data sources into a high-quality and accessible database that facilitates patient-centered research. Central to the data network is the authentic engagement of patients and caregivers as champions for their families. The data network includes 790 enrollees, 99 percent of whom are willing to be contacted to participate in research.

Presenting Patient Perspective at AHIMA Event

O’Boyle’s openness about her frustration with health records-related hassles caught the attention of officials from the GetMyHealthData.org initiative, which shared O’Boyle’s ordeal on its website. When the New York Times wrote about the Obama administration’s policies on electronic health records, they turned to O’Boyle for a quote, having read her account on GetMyHealthData.org. “And that kind of put me on the map for being an outspoken person about getting medical records,” O’Boyle says.

Last year AHIMA staff surveyed attendees of its previous Hill Day/Advocacy Summit on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, and one of the questions they asked members was what they wanted in a future keynote speaker. AHIMA members responded that they wanted to hear more from patients and their experiences with getting their records. GetMyHealthData.org suggested that O’Boyle could provide that much needed perspective for AHIMA. O’Boyle spoke at the 2018 AHIMA Advocacy Summit in March. Prior to the summit she didn’t know about AHIMA. She was happy to learn that there was an industry organization for health records professionals, one that could help her learn more about the regulations that need to be navigated to obtain records, and that understand the relevance of developing an ICD-10 code in the future. When O’Boyle learned about the role HIM professionals play in using and assigning ICD-10 codes, she immediately sought out more information, since having a code for Phelan-McDermid Syndrome would go a long way in creating awareness about the disease and the need for better treatments. The Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Foundation is currently looking into the process for requesting that an ICD-10 code for the syndrome be included in the code set (read more about the process for creating an ICD-10 code in the sidebar below). In July, two members of the Texas Health Information Management Association—Sarah Wilbert, RHIA, and Michelle Herman, RHIA—attended the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Foundation 2018 International Family Conference, held in Grapevine, TX. They provided detailed information about how patients and parents of patients should go about requesting medical records.

Creating a New ICD-10 Code Often Improves Rare Disease Research

Rare diseases like Phelan-McDermid Syndrome are at a disadvantage when it comes to capturing the attention of researchers and the organizations that fund them. But that doesn’t mean the money isn’t there for potential research, or that the people living with these diseases aren’t worthy of attention. While a disease doesn’t need to have an ICD-10 code to officially be recognized by insurance companies, physicians, or specialty societies, having a code makes it easier to research.

That’s why it always bothered Trish Stoltzfus, CCS, CDIP, system director, coding and HIM systems, at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pinnacle, that there was no code for the rare autoimmune disease her 24-year-old son Travis suffers from, called primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). PSC is a chronic liver disease of the bile ducts.

Stoltzfus says that in the days of ICD-9, she assumed there would be a shiny new code for PSC when ICD-10 was finally implemented. When it wasn’t included, she was disappointed but moved on. Then, when she attended a conference for PSC patients and caregivers, another woman asked what she did for a living. She responded with her standard explanation of what HIM is, but really piqued the other person’s attention when she got to the part of HIM that included coding. The woman explained that a researcher in Europe had contacted her about pursuing the creation of an ICD-10 code for PSC. And with that, Stoltzfus started researching the code creation process. She soon realized she only had two weeks to create and submit a proposal for the next meeting of the ICD-10 Coordination and Maintenance (C&M) Committee, which is convened by the National Center for Health Statistics two times per year to vet new codes.

A proposal requires a description of the code being requested, the rationale for why it’s needed, and clinical references and literature supporting that request. Stoltzfus wrote the HIM case, combined it with the clinical case, and sent it off. Shortly after that, someone from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) called her and said the code was being taken off the C&M Committee’s agenda because there was too much work to be done in differentiating PSC from totally separate diseases with similar sounding names and symptoms. With a lot of last minute maneuvering, Stoltzfus was able to convince the CDC to put the code proposal back on the agenda. She then made the trip to present her proposal at the C&M Committee meeting in September 2017 after studying past proposals for guidance.

Proposals to this committee also undergo a public commenting period, which gives organizations like AHIMA and other specialty societies time to comment on why they think a condition does or does not deserve a code.

Sue Bowman, MJ, RHIA, CCS, FAHIMA, senior director of coding policy and compliance at AHIMA, says there are all sorts of reasons a code can be rejected. “Sometimes it has to do with level of detail, beyond what’s needed in ICD-10 or whatever would be documented in a medical record. That’s a common rejection. Usually any that don’t fit within the structure of ICD-10, outside the scope, or codes that don’t fit in the system [are rejected],” Bowman says.

Stoltzfus argued that PSC needed its own code because for too long the diagnosis was only given a catch-all cholangitis code. Additionally, having a PSC-specific code would help healthcare providers identify PSC in their patients and recommend appropriate treatment options, as well as reduce confusion in the billing process.

Following her presentation in September 2017, Stoltzfus waited for several months with no word on her proposal. Finally, after sending multiple emails to the CDC, she got word in April 2018 that PSC finally had its own ICD-10 code: K83.01.

Stoltzfus says that prior to the approval of the code, if a doctor in her hospital wanted a report on all of the patients treated for PSC in a given year, she wouldn’t have been able to run a report. She would have had to give him a report on all the patients treated under the catch-all code. All that changed with the approval of the ICD-10 code. Stoltzfus estimates that there are about 30,000 people in the United States with the condition—though that estimate will be much easier to nail down now that an ICD-10 code exists.

O’Boyle’s long, arduous experience with the healthcare system in general—and pursuit of reliable and actionable health data in particular—should remind HIM professionals of the goals they share with healthcare consumers. An individual’s health records must be made available to them and their caregivers in the format that best meets the requester’s needs. A person may need lab results for their next appointment with a specialist, while another may need their record for a dataset that could be used to find a cure for a devastating disease.

O’Boyle’s mission with the registry work is in part to relieve the parents of Phelan-McDermid Syndrome patients from the burden of reproducing and gathering their extensive health records. Not because that task is unimportant, but because it comes on top of the already overwhelming job of providing 24-hour care for their children.

“The whole point [of gathering data from parents for a registry] is that researchers can go in and learn more about the patient and learn more about the syndrome which may lead to treatments,” O’Boyle says. “...In rare disease it’s really important to give access to researchers, give access to this kind of data. Our families are asked in our registries to fill out questionnaires but some researchers prefer clinician-provided data. In the data network we combine the data from the parents (from the registry) and the data from patients’ medical records. If they can get the information straight from the medical records, then it validates the parents’ data and often provides more details.”

By Mary Butler

Learn More About Phelan-McDermid Syndrome ResearchFor more information about the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Foundation and their work, visit www.pmsf.org. |